The Taxonomy of Problems

Taxonomy: Fantastic problems and where to find them

The world is filled with a wondrous variety of problems. Yet we use only one name for them all (two at a push). No more: this is where problem geeks, like me, come to register new and exciting types of problems:

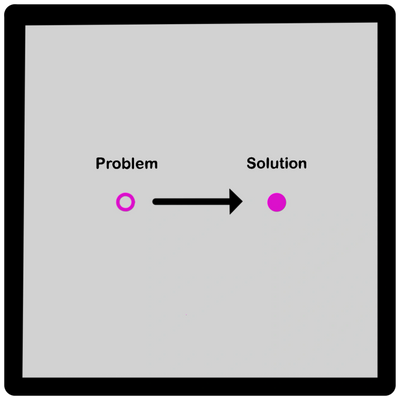

#1: The Shoestone

This is a single, simple problem that has a single, simple solution (E.g. If the problem is that a small stone in your shoe is causing you discomfort, the solution is to remove it). These are by far the most common type of problem. We encounter thousands of them every week.

Because of their ubiquity, it’s easy to mistake every problem for a shoestone. However, as we build our collection below, it will become clear that this is not the case: Our toughest problems, the ones that cause us the most angst, usually have solutions that are neither simple nor singular (if they have any solution at all). Treating such problems as shoestones is usually ineffective.

A Shoestone Problem, yesterday.

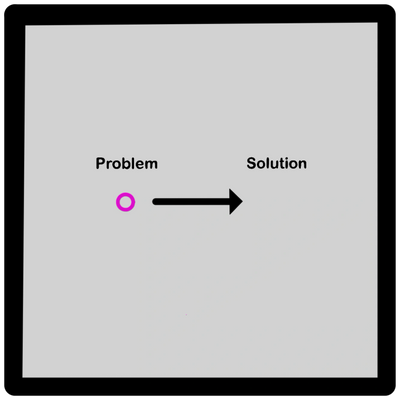

#2: The Unsolvable

Some problems don’t have a solution. They are the Unsolvables. In truth, we can rarely know for sure if any given problem is truly unsolvable, as an unexpected solution may appear sometime in the future.

So a problem like, for example, Maria, might appear to be unsolvable, but later discoveries reveal it to have instead been a tricky problem that could never have been solved at the time.

The Unsolvable. Often confused with the simply unsolved.

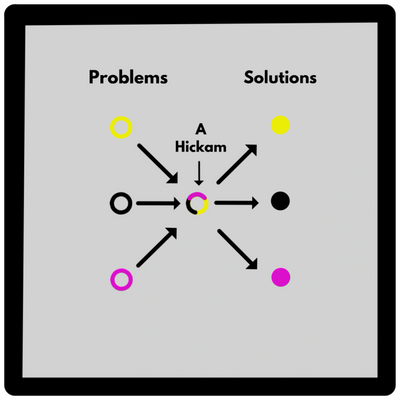

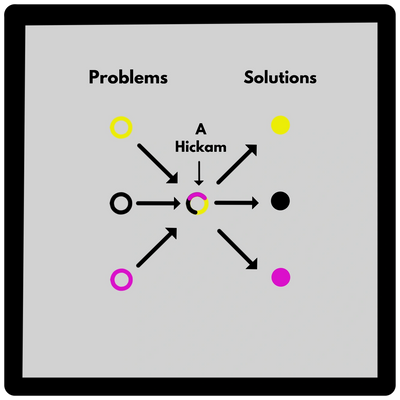

#3: The Hickam

This is a species of problem. Their defining feature is that they appear to be a single, shoestone (qv), but they are instead a collection of shoestones (or a collection of other, smaller hickams) that have clustered together to form one super-problem. This is nasty, because trying to solve a hickam in the same way you’d solve a shoestone frequently won’t work.

Hickams have many as-yet undocumented forms. Some require you to solve all of their underlying shoestones before the hickam itself is solved. Some can be reduced in size by solving some of its shoestones, but without requiring you to solve all of them. Recognising the existence of hickams is likely to be an important leap forward in improving your life.

The hickam takes its name from Dr John Hickam, MD. An influential 20th-Century figure in US medicine. ‘Hickam’s Dictum’, which he was renowned for drilling into his students, stated that “A man can have as many diseases as he damn well pleases.” This recognised the fact that doctors are often fooled by patients presenting the symptoms of two, unrelated illnesses at the same time.

A Hickam. Appears to be a single problem, but is actually a collection of smaller problems.

#3.1: The coincidental Hickam

A Coincidental Hickam forms when a two or more apparently unrelated shoestone problems (qv) randomly occur at the same place and time. They are then, mistakenly, believed to be one bigger problem - a Hickam - which can lead to the erroneous belief that they require a single solution, when in fact they need one each.

The Coincidental Hickam. Two or more smaller problems that have randomly joined to form a larger on

#3.2: The Critical-State Hickam

Borrowing from the Critical Point Theory of earthquakes, the Critical-State Hickam forms when one Shoestone problem (qv) triggers more Shoestone problems, which then trigger even more. In effect, the original problem has “gone viral”. Eventually a giant cluster of problems forms, which is then mistaken for a single problem. This leads to the assumption that it will have a single solution, when in fact it requires a cluster of solutions (a “Silver Cluster”, not a “Silver Bullet”).

The fact that any tiny Shoestone problem can snowball into an exponentially larger Critical-State Hickam means that the latter are all but impossible to predict. The best methods of avoiding them are to maintain spare capacity in order to solve smaller problems as they arise, and to operate systems and cultures in which many smaller problems are routinely prevented from happening in the first place.

The Critical-State Hickam: A small problem snowballs into a larger cluster of problems.

#4: The Squarepeg

Sometimes a tough problem does end up having a simple-looking silver-bullet solution. Why wasn’t it solved earlier then?

It’s because it wasn’t simple for those who were trying to solve it (even though it might appear so afterwards). This may be because they’re idiots or, more charitably, because they have the wrong type of expertise. Or it could be because it’s such a leftfield solution that no-one with any common sense would have dared try it (it required uncommon sense). So the technique here is simple: If you’re facing a tricky problem, get others to help. The more brains the better, and the more diverse the better too.

A Squarepeg Problem: Sometimes a tough problem has an obvious solution. Just not obvious to you…

#5: The Gateway

A problem whose solution solves many additional problems too.

This one can only be identified after the event, but it does point to a great principle: Almost any problem is worth the effort of solving. This is because the act of solving often yields insights that prove exponentially useful in unforeseen ways. Those organisations, teams and individuals who practice this no-problem-too-small philosophy tend to benefit from ‘emergent phenomena’ (which is chaos science’s baffling way of saying that they become more than the sum of their parts).

The Gateway Problem. Solve this, and the solution to several other problems will magically appear.

#6: The complex adaptive problem (a “cap”)

A CAP isn’t a problem, it’s a whole stack of problems. In fact, it’s worse: most CAPs are a stack of other CAPs. This means dealing with a CAP is like playing eternal Whack-a-Mole. No sooner have you batted away one part of the problem, but another pops up. And while you’re fixing that, the first one adapts and starts playing up again.

So what’s the answer?

The bad news is that, by definition, CAPs don’t have single, silver-bullet answers. You can’t expect to thrive as a person, a family, a business, a partner or a team if you’re holding out for one simple fire-and-forget solution to sort it all out.

So never mind the silver bullets (see?!), what you need to deal with a Complex Adaptive Problem is a Complex Adaptive Answer. A ‘CAA’ mimics the structure of a CAP: it’s a stack of answers that continually adapt too. Here’s how you can work one to manage your own worst CAP. See here…

#7: The Stic

The Stic takes its name from the Systems Thinking concept of Sensitivity to Initial Conditions.

The Stic itself isn’t a problem, it’s the seed of a problem. When the system it’s contained within is small. it’s bearable and therefore ignorable. But as the system grows and ages, the Stic gradually becomes a small problem, then a big one. Effectively it creeps up on the system, slowly reaching an unsolvable level before any attempt is made to solve it.

#8: The dearliza

The Dearliza is a cunning beast. At first sight it’s a relatively simple-looking problem (a Shoestone, qv), but it makes itself tough to solve by hiding behind a chain of other problems, each of which must be solved before tackling the original Dearliza.

Once you have solved the other problems, there is no time left to solve the Dearliza. Or you’ve forgotten all about it. So it lives to fight another day.

Dearlizas are commonly found around Dad-based DIY tasks. The Dearliza itself may be an annoying spot on the kitchen wall that needs repainting. So you fetch a paintbrush from the garage, but its bristles needs cleaning, so you wash it under the outdoor tap. But that’s started leaking over the winter, so needs fixing first. Off to the garage you go for the spanner. But the garage is irritatingly filled with excess cardboard boxes from Christmas, so they need breaking down and putting in the recycling. And, anyway, where was I? Oh yes, the spanner.

The Dearliza takes its name from the song ‘There’s a Hole in my Bucket’, which eulogises a particularly tough example of the species, which has made itself the solution to one of the other problems needed to solve it. Clever girl…

The Dearliza. A problem that distracts a would-be solver by hiding behind a series of other problems

Copyright © 2024 Never Mind The Silver Bullets - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy